WORDS:SUSANNAH SKIVER BARTON

Spirits additives have been in the news a lot lately, almost solely in relation to tequila. A clash between the independently run Additive Free Alliance and the Consejo Regulador del Tequila (CRT), tequila’s regulatory body, has chilled the growing movement for transparency in the category, and currently, per the CRT, no brands may legally discuss use or non-use of additives — which are legal — on their packaging or in their marketing. The stalemate seems likely to continue without a satisfying resolution unless and until the regulator and the industry can reach a compromise.

Meanwhile, many other spirits use additives, too, almost always without explicit disclosure: Cognac, rum, Scotch, and many more. Sometimes they employ caramel coloring to make a brand appear consistent from batch to batch, or to give the impression of greater cask influence. They may add sugar to sweeten a spirit or impart a rounder, more pleasing mouthfeel. Other additives can mimic the impact of prolonged oak aging, or layer on flavors to simulate more complexity.

The conflict in tequila has cast the issue of additives in black-and-white terms. For many spirits enthusiasts, additives are seen as deceptive, a way to cheat the natural processes at play in fermentation, distillation, and maturation. But that binary framework isn’t the only way of understanding the issue.

“Additives are not necessarily bad,” says Nicolas Palazzi, founder of PM Spirits, which imports tequila, rum, Cognac, and other spirits. “Yes, most of the time the product is subpar and therefore to make it more palatable … you need to put makeup on it.” But, he explains, there are other examples when using additives “makes a better product.” The key difference, Palazzi says, is “the way they’re used and why they’re used.”

Examining the legacy and tradition of additives across the spirits world can shed some light on the debate, even as it remains largely unsettled. The core issues at play — transparency and consumer choice — aren’t going away. And potential solutions could take a number of forms.

Whiskey’s History of Additives

Additive use in spirits was historically quite common. In the 19th-century United States, rectifiers added everything from prune juice to turpentine to their “whiskey” — often badly made or unaged spirit — to make it appear older or taste better. The practice directly led to the passage of the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897, which set the first standards for truth in labeling and made it clear to consumers that the whiskey in the bottle was unadulterated. Today, bourbon and other straight whiskeys are not allowed to contain any additives. Non-straight whiskeys and blends, including blends of straight whiskeys, may include up to 2.5 percent allowed coloring and flavoring materials without disclosure.

These are settled questions of law, and for the most part, whiskey drinkers aren’t clamoring for more information from brands — although there was a period, circa 2014–2015, when added flavoring in Templeton Rye became a flashpoint for what was then a new conversation about transparency in whiskey. A commentator named Steve Ury wrote a blog post at the time digging into whether ryes that did not include a “straight” designation might include added flavor. The exercise is still valid a decade, and many dozens of other brands, later, but doesn’t seem to stir up much conversation currently.

The additive that many drinkers do want to know about is caramel coloring, which is widely permitted outside straight American whiskey, including in heavily regulated categories like Scotch. It’s almost a guarantee that every blended Scotch, Irish, and Canadian whisky includes caramel for consistent color, as do many single malts and premium offerings, but there’s no requirement for disclosure. Still, some brands now tout “no added color” as part of their labeling and marketing — often alongside “non-chill filtered,” a Bat Signal for whiskey connoisseurs who believe the common practice has a negative impact on a whiskey’s flavor.

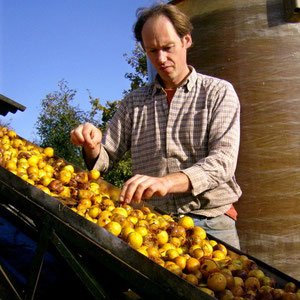

The Wide World of Rum Additives

Rum can contain caramel coloring, too, and often many other additives, though it is not a total free-for-all everywhere. Several rums are made under the rules of an established geographical indication (GI), including Jamaican, Cuban, and Demerara rums, as well as rhum agricole. GI-regulated rums typically eschew most additives, with the exceptions of caramel coloring — which is broadly permitted — and sugar, which several GIs allow. A major exception is the GI for Venezuelan rum, which allows “caramel, fresh or dry fruit macerations, bark, maceration of oak chips, and other approved substances.”

“If a brand puts that level of transparency and disclosure out there and the enthusiasts like it, they’re going to tell their friends. [They may be] half a percentage of your business, but they’re the ones talking to bartenders and bar managers.”

Beyond GI regulations, rum producers only have to work within the constraints of their permitting authority and those of the places they export to, which broadly means additives of all kinds may be used. Sugar is perhaps most common, not only because there’s historical precedent for it in many rum traditions, but because it’s widely favored by consumer palates.

“They’ve been [adding sugar] for hundreds of years,” says Matt Pietrek, rum expert and author of several books, including “Modern Caribbean Rum.” “Not in any attempt to deceive people; it’s more like, this tastes good and people like it.”

Palazzi agrees. “Most of the rums that people like are sweet, because they’re sweetened,” he says. “A lot of people feel that if the rum is dry there’s something wrong with it.”

Though Pietrek notes that he prefers dry, additive-free rums, he’s in favor of letting each producer make the rum they want. And he’d love to see producers across the rum world adopt some kind of transparency measure, like nutritional labeling, to give consumers more information about what’s in the spirit.

“Consumers can vote with their dollars,” he says, pointing out how Planteray includes a host of detailed information on the label, including how much dosage (added sugar) it includes. “Great! Literally any producer can do this.”

A Legacy in Cognac

For Cognac, in addition to caramel coloring, there’s a long tradition of adding both sugar and a substance called boisé, sometimes described as oak extract. All three additives may be aged before being blended with the spirit, though they aren’t necessarily. The use of boisé dates back to at least the 19th century and is rooted in what Amy Pasquet, one half of the husband-and-wife team at Cognac Pasquet, describes as a “waste-not, want-not” mentality. After distilling the spirit, wood chips left over from coopering were put into the still with water, their tannins serving to strip the interior of gunk. That liquid, rich with woody flavors, was then used to proof down the aged Cognac.

“Instead of saying we don’t add anything, we say everything is natural. Whiskey people really want that on the label.”

Nowadays, most boisé is produced commercially rather than in-house, and it’s likely widely employed in the leading houses. Many experts say boisé is not just an imitation of maturation. Ury, who shifted his attention from whiskey to brandy many years ago and now runs the Facebook group Serious Brandy, notes that it “may well be responsible for a lot of the rancio notes that people favor in Cognac.”

Although there are several independent, small Cognac houses — like Pasquet — that don’t use boisé or other additives, the substance’s longstanding legacy is respected by many connoisseurs like Ury. “It’s not as if [brands using boisé] are scam artists or something — it’s just a different way of doing things,” he says.

The rise in openly additive-free Cognac is relatively recent, spurred by whiskey enthusiasts migrating their attention to French brandy. Though it once made its own boisé, Pasquet stopped using additives in 2011; labels now state that the Cognac is hand-bottled, non-chill filtered, non-dosed, and natural color. “Instead of saying we don’t add anything, we say everything is natural,” Pasquet explains, noting that the brand’s German importer encouraged the labeling disclosure. “Whiskey people really want that on the label.”

Pasquet and its ilk represent a tiny fraction of overall Cognac volumes, but consumers’ desire for more information has penetrated even the big houses. A cohort of industry players that includes the likes of Hennessy, Rémy Martin, and Martell have agreed to voluntarily disclose ingredients, excluding boisé, on their labels or via QR code going forward. (VinePair reached out to the Bureau National Interprofessionnel du Cognac, the industry’s trade group, for clarification on why boisé is not included but has not received a response.)

How Many People Really Care, Though?

In spite of the furor of the additive debate among spirits enthusiasts, the issue isn’t even on the radar for the vast majority of consumers. “The people who really care are going to look for transparency and how the product is made and whether there are additives,” says Palazzi. “But there’s a lot of people who couldn’t care less.”

The average Hennessy VS drinker isn’t checking the label to see if there’s added sugar. Captain Morgan fans, if they stop to think about it, would likely accept without hesitation that the rum is full of flavoring. Only the hobbyists, those who self-identify as geeks, are concerned about whether their whiskey or brandy or rum has caramel coloring.

But although this group is a small minority, it’s often quite vocal — and usually willing to spend more on a bottle than the casual drinker. To a brand looking to cultivate that kind of engaged customer, playing up additive-free status can be a savvy marketing move.

“If a brand puts that level of transparency and disclosure out there and the enthusiasts like it, they’re going to tell their friends,” Pietrek says. “[They may be] half a percentage of your business, but they’re the ones talking to bartenders and bar managers. If you give them what they want, they will be your de facto brand ambassadors.”

And eventually, the movement that starts among the geeks can ripple outward. “Twenty-five years ago, no one cared about caramel in Scotch — that wasn’t a thing,” Ury says. Then enthusiasts started questioning the practice. “It was consumer-driven and you started seeing bottles saying ‘no coloring added,’” he says.

So even though the issue is moot for the majority of consumers, spirits brands still have to address it if they care about their most engaged fans. The conversation ultimately boils down to the broader issue of transparency, which has driven much of the consumer conversation in food and drink in the past few decades. People want to know what they’re putting in their bodies, and when brands don’t disclose that, mistrust can grow.

Piecemeal efforts from individual brands can be a workable approach, if they’re allowed to share information openly — something every category can currently do except for tequila. Potentially more effective are industry-wide moves like the one taking shape in Cognac. But the biggest game-changer would be mandated reporting from regulatory authorities like the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB).

The agency is currently considering a proposal to add certain nutrition facts to alcoholic beverages, similar to those found on food, including major allergens and calories per serving. But it stops short of requiring an actual ingredients list, and any public rollout is likely years away, if it ever occurs at all. For now, consumers looking for full transparency about a given spirit are largely at the mercy of individual brands. Those that talk openly about ingredients like additives serve as an example to others.

“I would love to see more transparency in Cognac,” Pasquet says. “We work for that day and night.”

https://vinepair.com/articles/examining-additives-in-spirits/