Once upon a time, David Avedissian wasn’t much of a booze aficionado. He never sipped spirits at home and rarely ever drank whiskey. “I would maybe order vodka at a bar,” he said. That all changed on a vacation to Kentucky in 2004, when he and his partner toured one of the state’s legendary bourbon distilleries.

“I drank bourbon for the first time on that trip,” he says. “I was like, ‘Woah.’ A light went off.” Avedissian started enjoying the popular, easy-to-find bourbons on the market, such as Maker’s Mark and Woodford Reserve.

Then one day, a friend told him to buy a special bottle of George T. Stagg, a limited-release bourbon named for a 19th-century whiskey pioneer. Even though it seemed pricey (around $50 at the time) he loved the taste. He ended up buying more bottles of George T. Stagg than he could open and drink.

Collectors like Avedissian, who started buying their bourbons in the aughts and early 2010s, have seen astronomical growth in value.

“I’ve never spent more than $200 on a bottle of whiskey,” he says. “Ever.”

That growth has happened because the sort of dude who once spent his coin on Bordeaux and Burgundy wines now desperately wants to become a Whiskey Bro. In many ways, spirits are a better investment than wine. Whiskey (or brandy or rum) has a much longer shelf life than wine—once a wine is open it must be consumed within a few days.

But bourbon prices have recently entered the stratosphere. So much so that a shadowy secondary market of flippers has emerged, with people selling coveted bottles for thousands of dollars.

“Bourbon is not just something you can consume. It’s a lifestyle. It’s a form of entertainment,” says Fred Minnick, author and bourbon expert.

Still, celebrity aside, the bourbon collector market is largely driven by a connected network of whiskey geeks—the Sneakerheads of the booze universe. In fact, collecting special whiskies is similar to collecting special edition sneakers. With bourbon, there’s always a new single-barrel offering, a special distillers selection, a rare vintage, or a limited edition label.

And just like in other collectibles markets, there is the manufacture of “collectibility.” Unlike in wine, where ratings on the 100-point scale by wine critics drive demand for top wines from Bordeaux or Barolo, the bourbon market is not moved by ratings and reviews in the same way. Avedissian says there have been numerous cases where limited-edition whiskeys have received terrible ratings from critics, but it didn’t matter.

“Scarcity matters,” he says, adding: “The demand and scarcity sometimes feels artificial.”

This scarcity is often created at the local level. Shops and bars around the country often make one-of-a-kind barrel selections. But now, private whiskey clubs, with a few dozen members, will combine buying power to select special barrels direct from distillers. Those barrels become a special limited run of a couple hundred bottles for club members, with some of the excess allocation going to a local retailer.

The real scarcity in bourbon derives from acquiring whiskeys from distilleries that no longer exist. For instance, specific bourbons made at Kentucky’s Stitzel-Weller distillery, which closed in 1992, are highly sought after. Stitzel-Weller is the distillery founded by the actual, nonfictional Julian “Pappy” Van Winkle.

That type of scarcity can’t last forever. Some collectors are thinking about what’s next. Minnick suggests that Armagnac, the brandy made in the French region of Gascony, might be the next big thing.

“In 10 years, Armagnac will be the buy of a lot of people who are bourbon drinkers,” Minnick says. “If I’m a collector, an investor, I’m chasing that. Someone who comes in and buys Armagnac would be like buying Pappy in 2004.”

That may be true, since Armagnac’s taste profile may appeal to the bourbon drinker.

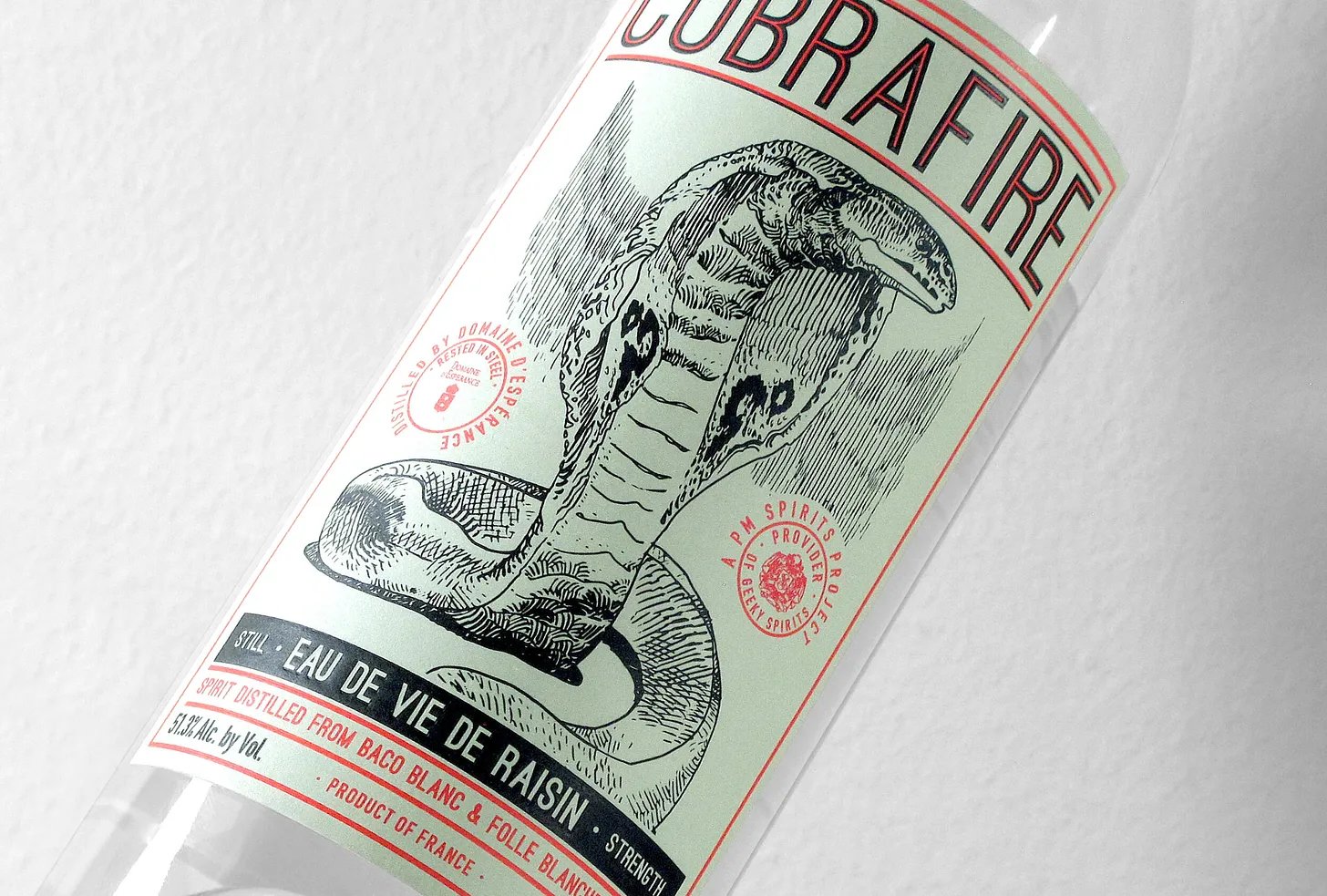

“There’s more Armagnac being sold, but it’s a very specific kind of Armagnac sold to a specific kind of buyer,” says Nicolas Palazzi of PM Spirits, who is a top importer of Armagnac. “We’re talking about Armagnac that’s very extracted, heavier on the wood, more powerful, more vanilla. So, it’s not very different than the whiskey that people are drinking.”

Right now, you can buy plenty of Armagnacs with 50 years of aging for less than $500 a bottle.

Michael Buffa, of the 200-member Orlando Whiskey Society, is one of these converts from whiskey to brandy. Buffa started a side group in central Florida with about a dozen people, called the Yak Pack, when his taste for Armagnac began to usurp his taste for whiskey.

“Armagnac has way more to offer than bourbon, personally,” he says. “In the secondary markets, what bourbon is selling for is absolutely ridiculous. Bourbon drinkers are very susceptible to trends.” The Yak Pack has already selected several brandy barrels. “The idea is to start creating buying power in brandy,” he says.

While the Yak Pack quickly gains experience and more exposure to brandy, Buffa notes this knowledge is rare. Whiskey brands have so many more reps out in the field doing so-called “education marketing.”

“Armagnac drinking for Americans is in its infancy,” Buffa says. “There really aren’t a lot of brandy experts.”